Your brain runs on oxygen the way a city runs on fuel. When a neighborhood gets busy, delivery trucks show up. Something similar happens in the cortex during demanding thinking. Blood brings extra oxygen to the regions doing the heavy lifting, and that shift can be measured with optical sensors placed on the scalp. The measurement is often called brain oxygenation, and it provides a practical window into cognitive load, the felt and measurable effort of a task. If you have ever tried to read dense text after a long day and felt your eyes glaze over, you already know what an overloaded brain feels like. This beginner friendly guide translates that feeling into understandable signals and shows how to use those signals to work and study with less strain.

We will start with what oxygenation actually measures, then connect it to the idea of cognitive load. After that, you will learn how the signals behave during real tasks, how to measure at home with simple routines, and how to turn numbers into useful habits. Along the way, you will see how a consumer headband can help, without turning the article into a commercial. The goal is not to chase perfect graphs. The goal is to make it easier to think clearly for longer, to recover quicker, and to save your best effort for the work that matters.

Contents

What Brain Oxygenation Actually Measures

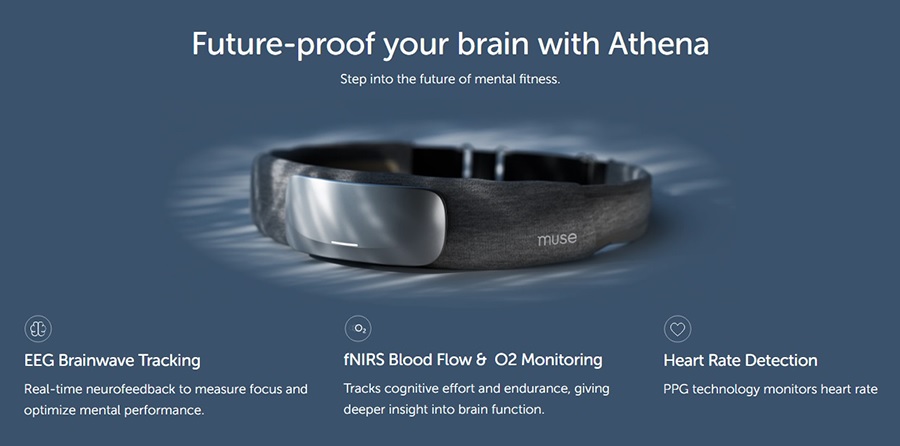

Functional near infrared spectroscopy, often shortened to fNIRS, uses near infrared light to estimate changes in oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin in the outer layers of the brain. The device sends harmless light into the scalp and measures how much light returns. Because oxygenated and deoxygenated blood absorb light differently, the system can infer when oxygen levels in a small patch of cortex rise or fall. When neurons in that patch become more active, local blood vessels dilate and deliver extra oxygen. This is part of a process researchers call neurovascular coupling, a partnership between neural activity and blood flow. You can think of it like a smart delivery service that sends more trucks to a busy street and fewer trucks to a quiet one.

The oxygenation signal is slow compared with electrical brain activity. The increase usually ramps up over a few seconds after the mental work begins, then settles into a plateau if the effort continues. When the task ends, the signal gradually returns toward baseline. This timing makes oxygenation a good match for blocks of effort that last longer than a quick glance or a single decision. Many daily activities fit this description. Reading a chapter, drafting an email, planning a meeting, or solving a set of math problems each unfolds over minutes, not milliseconds.

The measurement has boundaries you should know. Light scatters in tissue, so fNIRS is most sensitive to the surface of the cortex rather than deeper structures. Hair can block or scatter light, so careful placement of the optodes helps a lot. The signal is also influenced by the skin and scalp. Newer processing methods try to separate those effects, and even with simple consumer tools you can improve quality by keeping sensors steady and avoiding large head movements. None of these caveats make the signal useless. They simply remind us to treat the numbers as guides, not as verdicts.

What does this look like on a graph you might see at home. Imagine a short study session. You start with two minutes of relaxed breathing. The oxygenation trace sits near baseline. You open your notes and begin summarizing a chapter. Over the next ten to fifteen seconds, the line rises and levels off. During a brief pause to sip water, it dips slightly. When you tackle a tougher paragraph, it climbs again. After you close your notebook, the line eases back down. The graph mirrors your lived experience of effort. It does not read your mind, it simply reflects how hard a region is working to support the task at hand.

Cognitive Load, The Three Kinds You Meet At Work

Cognitive load is the mental effort required to learn a concept or complete a task. It affects your sense of strain, your performance, and your ability to remember what you just did. A classic way to understand load splits it into three parts: intrinsic, extraneous, and germane. Once you can spot each part, you can lower the unhelpful pieces and keep the helpful one. That is the heart of smarter studying and calmer workdays.

Intrinsic load comes from the task itself. Multiplying two large numbers in your head has more intrinsic load than adding two small numbers. Learning a new software framework has more intrinsic load than using a familiar one. You cannot erase intrinsic load without changing the task, but you can manage it by controlling difficulty and sequence. Chunking, scaffolding, and spaced practice are the friendly tools here. Think of them as trail markers that keep you from wandering into the thorny bushes.

Extraneous load is the mental effort created by poor design or distractions. Cluttered slides, unclear instructions, constant notifications, and noisy rooms add extraneous load. They do not help learning or performance. They just use up your limited attention budget. Reducing extraneous load is one of the fastest ways to feel smarter without changing your brain at all. A quiet space, a clear brief, and a tidy interface free up oxygen and neural resources for the work that matters.

Germane load is the good kind. It is the effort you invest in building stronger mental models, such as summarizing a chapter in your own words, teaching a concept to a friend, or deliberately comparing two solutions to a problem. Germane load can feel challenging in the moment, yet it pays off later because it strengthens understanding. You want more of it, within reason, especially once you have cleared away unnecessary extraneous load.

On a typical weekday, these three kinds of load mingle like players on a field. Imagine a team meeting about a new project. Intrinsic load comes from the complexity of the project itself. Extraneous load shows up as a chaotic agenda and email pings. Germane load appears when the group sketches a clean workflow and checks understanding. Brain oxygenation helps you see the cost of the situation. A long plateau at a high level can indicate that your prefrontal cortex is working too hard for too long. A moderate rise that settles during pauses can indicate a good balance between challenge and pacing. While oxygenation is not a score, it is a helpful narrator that describes how smooth or bumpy the road is as you drive.

How Oxygenation Reflects Load During Real Tasks

Oxygenation tends to rise with sustained mental effort in the regions supporting the task. The shape of that rise tells a story. A gradual climb toward a steady plateau often signals that you have matched the task with your current skills. You are working, not flailing. A sharp spike that stays high without relief can signal overload. Your brain is throwing resources at a problem without finding a rhythm. A small bump that quickly returns to baseline can signal underload. You might be coasting, bored, or distracted by easier side activities like inbox cleaning.

Here are three patterns you can watch for when you review a session:

- Steady state, a moderate rise followed by a level line with small waves. This often pairs with decent output and a sense of forward motion. You can maintain this for twenty to forty minutes if the task is well chosen.

- Spike and crash, a quick climb to a high level followed by a dip when you step away. This pattern often appears when you jump into a task with no plan or when distractions pile up. A short reset with breathwork or a clearer next step can transform the next block.

- Plateau and slide, a plateau that slowly drifts downward even though you keep working. Fatigue or loss of engagement might be the cause. Switching to a different task or taking a real break helps more than adding coffee.

These patterns are not medical diagnostics. They are coaching cues. Pair them with simple behavioral notes to make sense of your day. For example, write down what you worked on, what interrupted you, and when the task felt easy or hard. Over a week, you may notice that mornings produce a steady state curve on writing, while afternoons to late afternoons produce spike and crash on the same work. That discovery lets you place writing in the morning and leave meetings or light admin for later. No superhero willpower required.

Load is also task specific. Mental arithmetic can drive a different oxygenation response than visual design or language translation. Even within a single task category, difficulty and novelty matter. A first pass through a new topic often sits higher than a review pass. If you pair oxygenation with a simple attention measure, such as a cue from EEG or a self rating of focus every five minutes, you will see how engagement and effort interact. A sweet spot appears when attention feels steady and oxygenation holds at a moderate level with gentle rises during challenging moments. That is the zone many people describe as clear and productive.

Measuring At Home: Practical Protocols and Tips

Measuring brain oxygenation at home does not require a lab. It does require a sensible routine, patience, and a bit of curiosity. The aim is repeatability. If you can repeat the same setup every day for a week, you will get more useful insights than from a single long session with fancy gear. Start small, adjust as you learn, and keep notes you can actually read later.

Prepare your space

Pick a chair and a desk where you can sit comfortably. Place your device and notebook within reach. Silence notifications for the first block. If you share a home, let others know you are doing a short focus session so they do not accidentally interrupt you. Good light and a clean surface lower extraneous load immediately.

Set your baseline

Before you begin the task, take one to two minutes to settle. Breathe at a comfortable pace, roughly five to six breaths per minute if that feels natural. Keep your face relaxed and your shoulders down. This short baseline gives the oxygenation signal a quiet starting point so the later rise makes sense. If the line is already climbing during baseline, extend the calming period or adjust your posture.

Run short, clear blocks

Use blocks of ten to twenty five minutes, matched to task difficulty. Choose one goal per block, like summarizing two pages, solving five problems, or writing one paragraph. Label the block in your notes. During the work, avoid multitasking. If you hit a snag, write the snag on a sticky note and keep going. Your goal is a clean oxygenation picture with minimal detours. After the block, rest for three to five minutes. Stand up, look far away, and do a gentle shoulder roll. This is not punishment. It is brain friendly pacing.

Track simple context

Context turns numbers into understanding. In your notes, record sleep quality, caffeine, time of day, and any unusual stress. These tags will matter when you compare sessions. You might discover that a late start with poor sleep produces a higher plateau for the same task, or that a morning session after a walk produces a smoother curve. Make one change at a time. If you change everything, you learn nothing.

Common setup tips

- Keep sensors seated firmly against the skin. Adjust hair to allow good contact if needed.

- Avoid large jaw movements and head turns during the block. Gentle stillness is enough.

- Do not chase a perfectly flat baseline. Normal physiology has small waves. You are looking for trends, not zero noise.

- Review the entire session once. Do not stare at the live graph if it makes you anxious. Use audio or simple cues during the block, then check trends afterward.

From Numbers to Habits: Using Feedback to Pace Your Day

Data is only helpful when it changes what you do. The trick is to convert oxygenation patterns into small, repeatable habits. Think in terms of levers you can pull: block length, task sequencing, break style, and recovery. Keep each lever simple so you can tell which one made the difference.

Block length

If your curves often show a quick spike then a long high plateau, shorten the block and aim for a steady state pattern. Instead of thirty minutes, try eighteen. If your curves show a modest bump that drops too quickly, lengthen the block slightly or raise the challenge. The right block length changes over the day, so give yourself a morning setting and an afternoon setting.

Task sequencing

Tasks that demand heavy working memory, such as writing from scratch or learning new material, often fit best when you are fresh. Put them early. Lighter tasks, such as scheduling and email, fit later. If oxygenation stays high deep into the afternoon, insert a recovery block with movement and sunlight, then resume. Sequencing is not fancy. It is thoughtful ordering.

Break style

Not all breaks are equal. A scroll through headlines can keep your brain simmering. A short walk, a glass of water, a stretch, or two minutes of slow nasal breathing can let the line drift back toward baseline. Experiment with one break style per day and note which one produces the nicest reset.

Recovery and sleep

Across weeks, the most powerful change often comes from better sleep and regular movement. Oxygenation patterns tend to flatten after poor sleep and stabilize after good sleep. You do not need a study to feel that truth. Use the data as a reminder to defend bedtime and to get outside for light and motion.

Here is a simple day plan that many people find workable:

- Morning: two focus blocks on meaningful work, each fifteen to twenty five minutes, with calm breathing before each.

- Midday: movement break and food, then one administrative block.

- Afternoon: one more focus block or two lighter blocks, based on energy. If oxygenation stays high, switch to simple tasks.

- Evening: a short wind down with reading or guided breathing to signal recovery.