Cognitive effort is the felt cost of thinking. You notice it when a puzzle heats your forehead, when a third meeting taxes your patience, or when a complex email requires two passes before it clicks. Neuroscience gives us a helpful window here. As mental work increases, local brain networks request more energy. Blood flow and oxygenation shift to meet that request. With the right tools, those shifts can be measured, which turns a fuzzy feeling into a useful signal you can train around. The aim of this article is to connect the dots: what effort is, how blood oxygenation changes during hard thinking, which tools measure those changes, and how to use this knowledge to pace your day and build steadier focus without punishing marathons.

Contents

What We Mean by Cognitive Effort

Cognitive effort is the combination of demand, motivation, and control. Demand is the load a task places on working memory and attention. Motivation is the reason you stay with the task. Control is the top down guidance that helps you ignore distractions and correct errors. When these pieces stack up, you feel effort rise. Two different tasks can have the same objective difficulty, yet one can feel much harder because your sleep was short, your caffeine timing was off, or your values do not align with the goal. That is why effort is both a measurable process and a subjective experience.

Researchers often study effort with tasks that scale cleanly from light to heavy. Examples include mental arithmetic, n back working memory tasks, or color word conflict tasks that pit automatic reading against naming a font color. As the level rises, accuracy and reaction time change in predictable ways. Inside the head, cortical regions responsible for attention, language, or memory recruit more resources. Outside the head, people report the familiar sensations of strain: forehead warmth, jaw tension, and a subtle drive to switch to something easier. Connecting the inside and the outside builds better training plans.

Effort versus difficulty

- Task difficulty is the inherent complexity of the task, such as three digit subtraction versus single digit subtraction.

- Effort is the moment to moment cost you pay to meet that difficulty with your current energy, attention, and motivation.

- Two people can face the same difficulty and report very different effort levels. Context matters, sleep, mood, and practice history all weigh in.

Blood Oxygenation 101: From Neurons to Hemoglobin

Neurons run hot when they work. They need oxygen and glucose. When a brain area becomes active, nearby blood vessels respond, a process often called neurovascular coupling. Within a few seconds, there is an increase in oxygenated hemoglobin and a relative decrease in deoxygenated hemoglobin in the small vessels serving that region. This pattern can be detected with different technologies. Magnetic resonance imaging gives us the famous BOLD signal, which is sensitive to oxygenation changes. Functional near infrared spectroscopy, or fNIRS, uses gentle light at the scalp to estimate concentrations of oxygenated and deoxygenated hemoglobin in the outer layers of cortex. Both methods tie mental effort to a vascular response that can be tracked over time.

The key idea is simple: as cognitive demand rises, many tasks produce a larger bump in oxygenated hemoglobin in task relevant regions. For working memory, this may appear over parts of the frontal cortex. For language, this often shows up in temporal regions. fNIRS does not see deep structures, and it samples relatively slowly compared to electrical recordings, yet it offers a practical trade off: quieter, more portable, and friendly to real tasks at a desk. That makes it a useful companion for everyday experiments about workload. You can run a hard task, note the oxygenation shift, then change your pacing or breathing pattern and see whether the curve looks smoother.

Reading the curves without overthinking

- Oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO) tends to rise with effort, often peaking several seconds after a task begins.

- Deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) often falls slightly during the same window, then returns toward baseline during rest.

- Baselines matter: light movement, facial muscle tension, and posture can nudge the signal. Calm, consistent starting conditions help.

Tracking Mental Work With fNIRS and EEG Together

Each measurement tool is a different kind of microphone. fNIRS listens to the blood supply. EEG listens to fast electrical rhythms from large groups of neurons. When you put both views together, you get a more complete picture. During a working memory block, for example, you might see frontal HbO rise while EEG shows a shift in alpha and beta activity. The two signals are not redundant. They speak to different parts of the same story: demand rises, control networks engage, and vascular support follows.

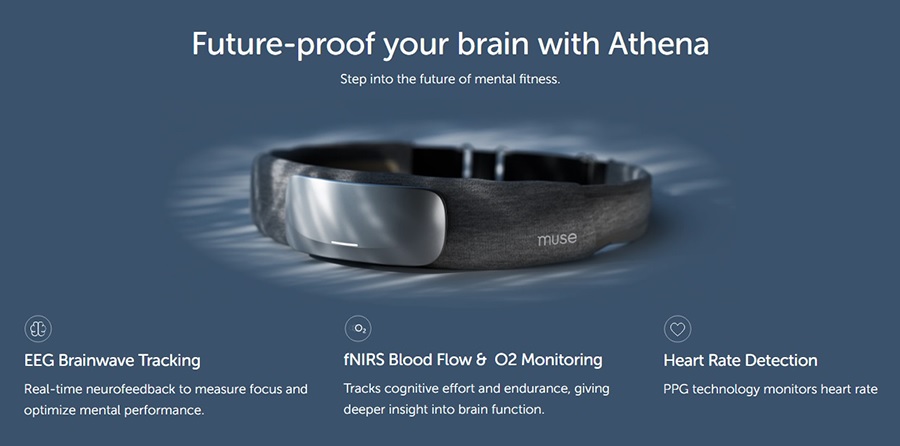

This pairing is useful for training. fNIRS can show whether your pacing keeps the vascular response stable rather than spiky. EEG can give immediate feedback about steadiness during the task. In research labs these signals are combined with controlled tasks. At home, people can approximate the spirit of this method with simpler tools. A consumer EEG headband, such as the Muse device, can offer audio cues during brief attention exercises. It does not diagnose conditions, and it is not a medical device, yet many users find that it helps them recognize when their mind is steady and when it is wandering. If you pair a short attention exercise with a structured task like mental arithmetic, you can practice noticing early signs of rising effort and adjust your strategy before quality dips.

Common task examples

- Mental arithmetic: read a three digit number, subtract by sevens, record accuracy, and note effort on a simple one to ten scale.

- Working memory: hold a short list of letters, then decide if a new letter matches one from a few steps back.

- Conflict control: name the font color of words that sometimes spell a different color. This taxes control and reveals fatigue quickly.

Practical Uses at Home and Work

The biggest win is smarter pacing. If you treat cognitive effort like fuel, you can plan routes that do not leave you stranded. High effort tasks should not sit back to back without recovery. Short, targeted breaks, especially ones that shift your sensory input, protect quality. Looking out a window to a far horizon, drinking water, standing to stretch calves and hips, and two minutes of slow breathing all help reset your baseline. The goal is to keep your curve steady, not flat. A day with controlled waves beats a day with one giant spike and a late crash.

Teams can use these ideas to shape meetings and deep work time. Place planning sessions earlier in the day when group control is stronger. Reserve late afternoons for lighter collaboration, document edits, or review tasks. If your role requires constant switching, build two protected blocks of single task time and defend them kindly. You can even create a simple effort budget. Assign a rough cost to common tasks, for example, hard writing equals 3 units, email triage equals 1 unit, a performance conversation equals 4 units. Cap your day at a reasonable total and see how your mood and output respond.

Simple self monitoring toolkit

- RPE for thinking: rate perceived effort, one to ten, at the end of each focused block.

- Quality marker: record accuracy or a quick yes or no for whether the block reached its goal.

- Breath and posture: start each block with ten breaths at a 4 and 6 pace and a tall, relaxed posture. Many people see steadier effort curves when they pair these basics with work.

Getting Started: A Four Week Plan

This plan teaches your system to sense effort early, to adjust before quality drops, and to finish the day with gas in the tank. Keep sessions short. Hold a friendly tone. Write down what helps and repeat it. If you have a neurological condition, headaches, or a seizure history, check with a clinician before you add any specialized equipment or ambitious drills.

Week 1, notice and name

- Pick two daily focus blocks of 20 to 25 minutes. Start with ten slow breaths, then work on a single target.

- Rate perceived effort and quality after each block. Add one sentence about posture, light, and interruptions.

- End of week reflection: identify the hour of the day when effort feels lightest. Protect it next week.

Week 2, pace and protect

- Place your most demanding task in the lightest hour you discovered. Insert a three to five minute sensory reset between heavy items.

- Add one short movement snack after lunch, for example a brisk five minute walk or ten slow squats, adjusted for your body.

- If you own a consumer EEG device such as the Muse headband, try a five minute attention exercise before your hardest block, then note whether effort ratings or quality change.

Week 3, train under controlled load

- Introduce one structured challenge task, such as mental arithmetic. Keep it short. The aim is to notice early signs of rising effort, not to push to exhaustion.

- Track sleep timing and caffeine. Many spikes in effort are sleep or timing problems in disguise.

- Refine your break recipe. Some people recover better with quiet, others with a short conversation or a short walk in daylight.

Week 4, personalize and automate

- Pick the two practices with the biggest impact. Put them on repeat with calendar anchors and visible cues on your desk.

- Build a modest effort budget for the week ahead. Spread heavy items, leave room for surprises, and keep one low effort win in your pocket for the afternoon slump.

- Plan a small celebration for finishing strong, like a phone free walk or a favorite playlist during chores. Positive endings teach your brain to come back tomorrow.