Iron is an essential mineral that plays a crucial role in various bodily functions, including the production of red blood cells and the regulation of cell growth. However, excessive iron accumulation, known as iron overload, can lead to a host of health complications. While the physical manifestations of iron overload are often discussed, its impact on cognitive health remains a lesser-known aspect.

Contents

What is Iron Overload?

Iron overload, also known as hemochromatosis, is a medical condition characterized by the excessive accumulation of iron in the body [1]. This build-up can lead to various health issues, ranging from mild to severe, and may even be life-threatening if left untreated. Understanding the different types, causes, symptoms, and complications of iron overload can help in its timely identification and management.

Definition and Causes

Iron overload can result from two primary sources: hereditary (primary) and acquired (secondary) conditions.

Primary Iron Overload: Hereditary Hemochromatosis

Hereditary hemochromatosis is a genetic disorder in which the body absorbs too much iron from the diet. This excess iron is then stored in various organs, such as the liver, heart, and pancreas, causing damage over time. The most common form of hereditary hemochromatosis is caused by mutations in the HFE gene, which regulates iron absorption in the body.

Secondary Iron Overload: Acquired Conditions

Secondary iron overload occurs as a result of other underlying medical conditions or treatments that affect iron metabolism or lead to increased iron intake. Some common causes of secondary iron overload include frequent blood transfusions, chronic liver diseases, excessive iron supplementation, and certain anemias, such as thalassemia or sideroblastic anemia.

Symptoms and Complications

The symptoms of iron overload can be nonspecific and may develop gradually, making it challenging to detect the condition in its early stages. Some common symptoms include fatigue, joint pain, abdominal pain, and loss of libido. As iron accumulates in the body, it can lead to more severe complications, such as liver cirrhosis, diabetes, heart problems, and hormonal imbalances.

In addition to these physical complications, iron overload can also impact cognitive health, leading to cognitive decline and an increased risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases.

Diagnosis and Treatment Options

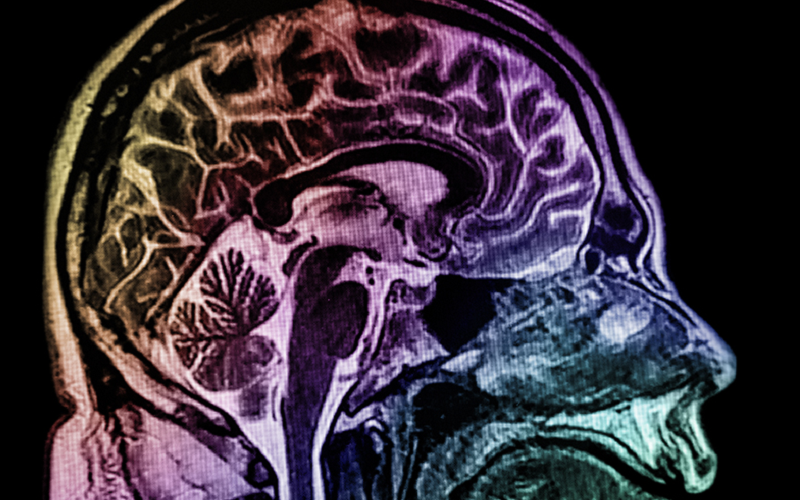

Diagnosing iron overload typically involves blood tests to measure serum ferritin (a protein that stores iron) and transferrin saturation levels. In some cases, genetic testing may be recommended to identify hereditary hemochromatosis. Imaging studies, such as MRI, can also help assess the extent of iron accumulation in the liver and other organs.

Once a diagnosis is established, treatment options for iron overload aim to reduce excess iron levels in the body and manage any related complications. Therapies may include phlebotomy (periodic blood removal), iron chelation medication, and dietary changes to reduce iron intake. Early detection and prompt treatment can help prevent long-term damage to organs and cognitive function.

Cognitive Decline: A Brief Overview

Cognitive decline refers to a gradual decrease in cognitive function, encompassing various aspects of mental processing such as memory, attention, problem-solving, and language skills [2]. This decline can be a natural part of the aging process or a result of other factors, including medical conditions and lifestyle choices. Understanding the causes, risk factors, and impacts of cognitive decline is crucial for developing prevention and management strategies.

Definition and Symptoms

Cognitive decline is characterized by a progressive deterioration of cognitive abilities, which can manifest in various ways. Some common symptoms include forgetfulness, difficulty concentrating, challenges in decision-making, and problems with language and communication. The severity and progression of cognitive decline can vary greatly among individuals, with some experiencing only mild effects, while others may develop more significant impairments.

Causes and Risk Factors

Several factors can contribute to cognitive decline, including age, genetics, lifestyle choices, and medical conditions. Some of the key risk factors for cognitive decline include:

- Aging: As people age, the brain undergoes structural and functional changes that can result in a decline in cognitive abilities.

- Genetics: Family history and certain genetic factors can increase the risk of cognitive decline and dementia.

- Medical conditions: Conditions such as iron overload, hypertension, diabetes, and high cholesterol can impact brain health and cognitive function.

- Lifestyle choices: Factors like poor diet, physical inactivity, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption can also contribute to cognitive decline.

The Science Behind the Iron Overload and Cognitive Decline Connection

The connection between iron overload and cognitive decline is a complex interplay of multiple factors. By exploring the role of iron in the brain, the impact of oxidative stress and inflammation, blood-brain barrier dysfunction, and the association with neurodegenerative diseases, we can better understand this critical relationship.

Iron’s Role in the Brain

Iron is a vital component in various brain functions, including neurotransmitter synthesis, myelin production, and energy metabolism [3]. As a cofactor for numerous enzymes, iron helps maintain normal cognitive functioning and brain development.

Despite its essential role, excessive iron accumulation in the brain can have deleterious effects. Unbound iron can catalyze the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to oxidative stress, cellular damage, and inflammation, ultimately contributing to cognitive decline and neurodegeneration.

Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

The overproduction of ROS due to excessive iron can overwhelm the brain’s natural antioxidant defense mechanisms, resulting in oxidative stress. This oxidative stress can damage neurons, disrupt cellular function, and cause neuroinflammation. Chronic inflammation, in turn, can exacerbate cognitive decline by further damaging brain cells and impairing their ability to communicate effectively.

Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a semi-permeable membrane that separates the brain’s blood vessels from its extracellular environment, protecting the brain from potentially harmful substances. Iron overload can disrupt the integrity of the BBB, allowing harmful substances and inflammatory molecules to enter the brain, thereby contributing to neuronal damage and cognitive decline.

Neurodegenerative Diseases and Iron Overload

Research has established links between iron overload and various neurodegenerative diseases, which are characterized by progressive cognitive decline [4].

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia, is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. Studies have found elevated iron levels in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, suggesting a potential role for iron in the disease’s pathogenesis.

Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease is a neurodegenerative disorder marked by the progressive loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra, leading to motor and cognitive impairments. Research indicates that iron accumulation in the substantia nigra may contribute to oxidative stress and neuronal death in Parkinson’s disease.

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disorder that affects the central nervous system, causing inflammation and damage to the myelin sheath surrounding nerve fibers. Studies have shown that iron accumulation in the brains of multiple sclerosis patients can contribute to neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration, further exacerbating cognitive decline.

Identifying the Iron Overload Hidden Risk Factor

Given the complexity of the relationship between iron overload and cognitive decline, it is crucial to identify and address this hidden risk factor. Early detection, screening for at-risk populations, and lifestyle changes can all help mitigate the cognitive decline risk associated with iron overload.

The Importance of Early Detection

Early detection of iron overload is essential in preventing and managing its impact on cognitive health. By identifying iron overload in its initial stages, appropriate interventions can be implemented to reduce iron levels, minimize oxidative stress and inflammation, and maintain cognitive function [5].

Iron Overload Screening for At-Risk Populations

Screening for iron overload in individuals at higher risk can facilitate early detection and intervention. At-risk populations include those with a family history of hereditary hemochromatosis, individuals who receive frequent blood transfusions, and those with a history of iron supplementation or conditions that affect iron metabolism. Regular blood tests to measure serum ferritin and transferrin saturation levels can help identify iron overload in these populations.

Lifestyle Changes to Mitigate Cognitive Decline Risk

In addition to early detection and management of iron overload, adopting a healthy lifestyle can also help reduce the risk of cognitive decline. Some beneficial lifestyle changes include:

- Diet: Consuming a balanced diet low in iron-rich foods, such as red meat and fortified cereals, can help manage iron levels in the body. Incorporating foods rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory nutrients, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats, can also support brain health.

- Physical activity: Engaging in regular physical exercise can improve blood flow to the brain, reduce inflammation, and promote the growth of new brain cells.

- Mental stimulation: Participating in cognitively challenging activities can help maintain cognitive function and resilience in the face of potential decline.

- Stress management: Practicing stress reduction techniques, such as mindfulness meditation or yoga, can lower inflammation and support overall brain health.

Iron Overload Treatment and Management Strategies

Once iron overload is identified as a contributing factor to cognitive decline, appropriate treatment and management strategies can be implemented to reduce iron levels, alleviate oxidative stress and inflammation, and support cognitive health. These strategies may include iron reduction therapies, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory approaches, and cognitive and behavioral interventions [6].

Iron Reduction Therapies

Phlebotomy

Phlebotomy, the process of periodically removing blood from the body, is a standard treatment for reducing excess iron levels. By removing blood, the body is forced to utilize stored iron to produce new red blood cells, thus lowering overall iron levels. The frequency of phlebotomy sessions depends on the severity of the iron overload and the patient’s response to treatment.

Chelation Therapy

Chelation therapy involves the use of medications that bind to excess iron, allowing it to be removed from the body through urine or feces. This treatment option may be recommended for individuals who cannot undergo phlebotomy due to medical reasons or for those with secondary iron overload.

Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Approaches

Incorporating antioxidant and anti-inflammatory treatments can help mitigate the effects of iron-induced oxidative stress and inflammation on cognitive health. These approaches may include dietary changes, supplementation with antioxidant vitamins (such as vitamin C and E), and the use of anti-inflammatory medications or natural compounds (such as curcumin or omega-3 fatty acids).

Cognitive and Behavioral Interventions

In addition to addressing the underlying iron overload, cognitive and behavioral interventions can be implemented to support cognitive health and functioning. These interventions may include:

- Cognitive training: Structured mental exercises designed to target specific cognitive abilities, such as memory, attention, or problem-solving, can help improve cognitive function and slow the progression of cognitive decline.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT): CBT can help individuals cope with the emotional and psychological challenges associated with cognitive decline, improving overall well-being and quality of life.

- Support groups: Joining a support group for individuals with cognitive decline or their caregivers can provide emotional support, practical advice, and a sense of community.

References

[1] Hemochromatosis – Symptoms and causes – Mayo Clinic

[2] Mild Cognitive Impairment: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments

[3] The impact of brain iron accumulation on cognition

[4] The role of iron in brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders

[5] Researchers find potential cure for deadly iron-overload disease

[6] Outcome of iron reduction therapy in ex-thalassemics