In our bustling world, achieving a restful night’s sleep can sometimes feel like an unattainable luxury. But what many might dismiss as just another byproduct of modern life may have profound implications for our cognitive health. Chronic sleep disruption (CSD) is more than just daytime drowsiness and irritability; it’s a silent adversary that can stealthily erode our memory functions. Yet, its significant role in memory decline remains alarmingly underappreciated.

Contents

- Introduction to Chronic Sleep Disruption and Memory Decline

- Understanding Memory Function

- The Science Behind Sleep and Memory

- Effects of Chronic Sleep Disruption on Memory

- Preventing and Mitigating Effects of Sleep Disruption

- References

Introduction to Chronic Sleep Disruption and Memory Decline

In today’s ever-evolving, fast-paced world, sleep often becomes a secondary concern, pushed aside for seemingly more pressing matters. Yet, the ramifications of consistently disrupted sleep patterns may be more significant than many realize. When we speak of chronic sleep disruption (CSD), we’re delving into a realm that goes beyond simple fatigue and reaches into cognitive territories that underpin our very essence. Memory, a crucial facet of our cognitive toolkit, is particularly vulnerable.

Definition of Chronic Sleep Disruption (CSD)

Chronic Sleep Disruption refers to persistent interruptions in one’s sleep pattern. This doesn’t just mean a few restless nights here and there. Instead, CSD is characterized by regular disturbances that prevent an individual from achieving the deep, restorative stages of sleep needed for optimal brain function. Whether these disruptions arise from external factors, like noise disturbances, or internal factors, such as sleep apnea, the outcome is a compromised sleep quality over an extended period.

Overview of Memory Decline and Its Impact on Daily Life

Memory decline isn’t just about forgetting names or misplacing keys. It encompasses a broader spectrum of cognitive lapses, from difficulty recalling recent events to challenges with spatial recognition. These declines can significantly affect an individual’s daily life. Imagine struggling to remember essential tasks at work, or finding it challenging to navigate familiar routes in your neighborhood. The progression of memory deterioration can result in reduced independence, lowered self-confidence, and even pave the way for more serious neurodegenerative conditions.

The Connection Between CSD and Memory Decline

Emerging research is continually shedding light on the intricate relationship between sleep and memory. Sleep, it appears, is not merely a passive state but an active process that plays a pivotal role in the consolidation of memories. Disturb this delicate process with chronic sleep interruptions, and the foundation of memory begins to wobble [1].

Understanding Memory Function

Before diving into the intricate relationship between sleep and memory, it’s essential to establish a foundational understanding of how memory operates. Memory isn’t just a singular function but a complex system that involves multiple processes working in tandem. Whether it’s recalling a loved one’s birthday, the taste of your favorite dish, or the feeling of a past experience, the steps your brain takes to retrieve these memories are much the same.

Basics of Memory Processing

Memory processing can be broadly divided into three primary stages: acquisition, consolidation, and retrieval. Each of these stages plays a crucial role in how we gather, store, and access information.

Acquisition

The first step in the memory process is acquisition. This phase involves experiencing and initially registering the information. Imagine attending a workshop; the notes you take and the information you hear during the seminar represent the acquisition of new knowledge. At this point, the data is stored in the short-term memory, a transient form of memory with limited capacity and duration.

Consolidation

Post-acquisition, for the memory to be useful in the long run, it needs to be transferred to long-term memory storage. This transition from short-term to long-term memory is termed consolidation. It’s during this stage that neural connections in the brain strengthen, creating a more permanent record of the information. The process of consolidation can span from minutes to years, with repeated exposure to the information aiding in its longevity.

Retrieval

The final step in the memory process is retrieval, wherein the consolidated information is accessed and brought to the conscious mind. Think back to the workshop example; if, after a few weeks, you can recall and discuss the topics covered, you’ve successfully retrieved that consolidated information from your long-term memory.

The Role of Sleep in Memory Processing

Sleep isn’t just a time for the body to rest; it’s a period during which the brain undergoes a multitude of processes crucial for cognitive health. Among these processes, memory stands out as a principal beneficiary [2].

During sleep, particularly in the deep stages, the brain busies itself with sorting and storing the day’s experiences. Neural pathways responsible for memories are reactivated, strengthened, or pruned to make way for new information. In a sense, sleep acts like a librarian, cataloguing, organizing, and shelving the day’s acquired knowledge into the vast library of our minds. Without adequate sleep, this librarian struggles, leading to misplaced, weakened, or even lost memories.

The Science Behind Sleep and Memory

Going deeper into the realm of neuroscience, the interplay between sleep and memory starts to unveil its complexities. Each phase of our sleep cycle plays a role in how our brain processes, refines, and stores information. For the layperson, the intricacies of this relationship might seem overwhelming, but with a closer look, the puzzle pieces begin to fit together in a coherent pattern.

Role of the Sleep Cycle in Memory Consolidation

Our sleep isn’t a homogenous block of rest. Instead, it’s segmented into different phases, each contributing uniquely to our overall health. When it comes to memory, two specific stages of sleep hold paramount importance: Rapid Eye Movement (REM) sleep and Slow-Wave Sleep (SWS).

The Importance of REM Sleep

Rapid Eye Movement sleep, often associated with vivid dreams, is a phase where our brain’s activity closely resembles its waking state. Yet, despite the flurry of neural action, our body remains in a state of paralysis. REM sleep plays a crucial role in consolidating procedural memories — the memories related to skills and habits, like riding a bike or playing the piano.

During REM, the brain integrates these procedural memories into our neural architecture, solidifying the learned skills. Studies have shown that individuals deprived of REM sleep after learning a new skill often struggle with recalling or perfecting that skill the following day.

The Role of Slow-Wave Sleep

Slow-Wave Sleep, also known as deep sleep, is characterized by synchronized, slow neural oscillations. This sleep stage is vital for consolidating declarative memories, which are memories related to facts and events. For instance, remembering historical dates or recalling a friend’s wedding hinges on the quality of our SWS.

During SWS, the brain undergoes a process of “replay,” where neural patterns experienced during the day are reactivated. This reactivation helps strengthen the neural connections associated with these memories, moving them from short-term storage regions to more permanent areas in the brain.

Brain Structures Involved

Beyond the stages of sleep, the specific areas of our brain engaged in these processes also warrant attention. Two primary regions come to the fore when discussing sleep and memory: the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex [3].

Hippocampus and Memory Formation

Situated deep within the brain, the hippocampus acts as the hub for short-term memory storage and plays a pivotal role during the consolidation phase. During the day, the hippocampus actively registers and temporarily stores new experiences. Then, during sleep, especially during SWS, it works in conjunction with other brain areas to transfer these memories to long-term storage sites.

Role of the Prefrontal Cortex

The prefrontal cortex, located at the brain’s front, is associated with higher-order functions like decision-making, reasoning, and, importantly, long-term memory retrieval. During SWS, the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus engage in a sort of dialogue, with the hippocampus “replaying” the day’s events and the prefrontal cortex facilitating their long-term storage.

Effects of Chronic Sleep Disruption on Memory

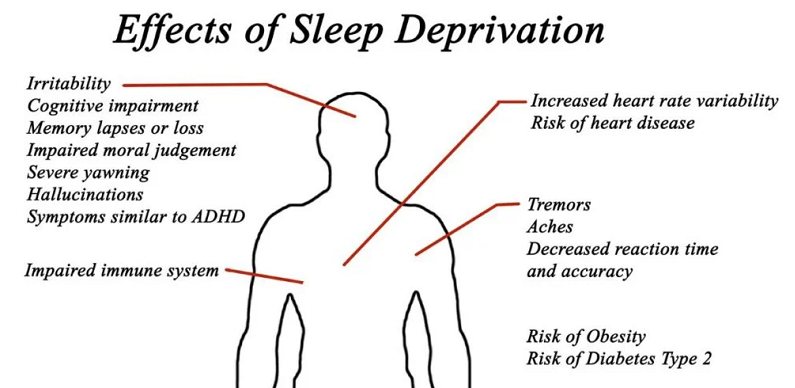

While the connection between sleep and memory formation seems abstract and largely “behind the scenes,” the repercussions of chronic sleep disruption (CSD) manifest in ways that are both tangible and often distressing. Beyond mere forgetfulness, consistent disturbances in our sleep cycles can precipitate a cascade of cognitive challenges. The effects, both immediate and long-term, underscore the crucial need to prioritize consistent, restorative sleep.

Immediate and Short-Term Impact

It’s no surprise that after a night of tossing and turning, our cognitive abilities are not at their peak. However, the short-term effects of CSD on memory and cognition extend further than many realize [4].

Reduced Concentration

Sleep deprivation doesn’t just leave one groggy; it directly impairs attention and focus. This lack of concentration hampers the acquisition phase of memory. If one can’t concentrate on new information or experiences, the foundation for memory formation is inherently weakened.

Impaired Memory Retrieval

Even if information was previously well-consolidated, sleep disruptions can make accessing that information challenging. Individuals may experience instances of “it’s on the tip of my tongue,” struggling to retrieve names, dates, or specific details that would typically come to mind with ease.

Long-Term Consequences

Beyond the immediate aftermath of a restless night, chronic sleep disturbances can have more insidious, long-term effects on memory and overall brain health.

Neurodegenerative Diseases

Research has highlighted a concerning link between chronic sleep disturbances and an increased risk for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. During deep sleep, the brain undergoes a cleaning process, clearing out waste products, including harmful proteins like beta-amyloid. Continuous sleep disruptions can impede this cleanup, leading to an accumulation of such proteins, which are associated with Alzheimer’s.

Structural Brain Changes

Chronic sleep deprivation isn’t just a functional issue; it can also lead to structural changes within the brain. Studies have shown that extended periods of poor sleep can result in a reduction in the size of the hippocampus, the very region crucial for memory formation and consolidation.

Behavioral and Psychological Effects

Memory decline stemming from CSD doesn’t exist in isolation. Often, it’s accompanied by behavioral and psychological shifts that further exacerbate cognitive challenges.

For instance, chronic sleep disruption can lead to mood disturbances like depression and anxiety. These mood disorders, in turn, can further impair cognitive functions, creating a feedback loop of deteriorating mental health and memory capabilities. Moreover, increased irritability, reduced motivation, and a decreased ability to handle stress can further cloud judgment and hinder memory processes.

Preventing and Mitigating Effects of Sleep Disruption

Recognizing the profound effects of chronic sleep disruption on memory is only the first step. The journey towards cognitive preservation demands proactive measures to prevent these disruptions and, for those already in the throes of inconsistent sleep, strategies to mitigate the consequences. Fortunately, by combining science-backed practices with lifestyle adjustments, it’s entirely possible to reclaim restful nights and safeguard our precious memories.

Establishing a Consistent Sleep Schedule

Our bodies thrive on routine, and this principle applies profoundly to our sleep-wake cycle. By adhering to a consistent schedule, you attune your body’s internal clock, making falling asleep and waking up more natural and restorative [5].

Prioritize Regularity

Whether it’s a weekday or weekend, try to go to bed and wake up at the same time. This regularity reinforces your body’s circadian rhythm, optimizing sleep quality.

Monitor Naps

While short power naps can be rejuvenating, long or irregular napping during the day can negatively affect your nighttime sleep quality. If you do nap, try to keep it brief and avoid napping late in the afternoon.

Optimizing the Sleep Environment

Your sleeping environment plays a significant role in determining how well you sleep. Factors like temperature, noise, and light can be controlled to create an optimal sleeping ambiance.

Create a Dark, Quiet, and Cool Space

Darkness signals to your body that it’s time to rest. Blackout curtains, earplugs, or white noise machines can aid in creating a sleep-conducive environment. Ideally, set the room temperature slightly cooler, as a drop in body temperature can facilitate sleep.

Invest in Comfort

A quality mattress and pillow can make a world of difference. If you frequently wake up with aches or feel unrested despite long hours in bed, it might be time for an upgrade.

Embracing Relaxation Techniques

In today’s high-stress world, winding down mentally is as crucial as the physical preparation for sleep.

Mindfulness and Meditation

Practices like mindfulness meditation can help in calming an active mind, preparing it for rest. Even a short session before bedtime can lead to improved sleep quality.

Avoid Stimulants Before Bed

Limiting caffeine intake in the hours leading up to bedtime and avoiding heavy meals can significantly impact your ability to fall asleep. Remember, substances like nicotine and certain medications also act as stimulants.

Seeking Professional Help

If sleep disturbances persist despite personal interventions, it might be time to seek professional guidance.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I)

CBT-I is a structured program that helps individuals address the thoughts and behaviors that prevent them from sleeping well. It’s a first-line treatment for chronic insomnia, with many patients benefiting from improved sleep patterns.

Sleep Studies and Clinics

For those suspecting they might have sleep disorders like sleep apnea, visiting a sleep clinic can provide clarity. These clinics use specialized tools to monitor your sleep, providing insights and actionable recommendations.

References

[1] Memory and Sleep

[2] Sleep deprivation induces fragmented memory loss

[3] Too little sleep, and too much, affect memory

[4] Association Between Sleep Duration and Cognitive Decline

[5] he Devastating Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Memory